smoke forecast 5am Saturday

Results 301 to 325 of 1123

Thread: Wildfire 2021

-

07-01-2021, 05:32 PM #301

-

07-01-2021, 06:24 PM #302

-

07-01-2021, 06:51 PM #303

Thinking about the politics of federal fire mgmt, I wrote this paper 11 years ago for my community college Engrish 101…

US Forest Service Firefighting:

Misplaced Priorities, Misappropriated Funds

By

Ill-Advised Strategy

Professor Thompson

English 101

9 December 2009

Thesis statement: To best serve the public, the US Forest Service should relinquish its fire suppression mission to local emergency management agencies.

US Forest Service Firefighting:

Misplaced Priorities, Misappropriated Funds

In recent years, sometimes several times a year, large wildland fires have captured the attention of the nation at large. Dramatic images of lost lives and burnt homes grab headlines, while shock waves of exhausted budgets and shifted priorities ripple through the land management agencies. Open fire on our nation’s public lands is hardly a new phenomenon; however, catastrophic fire emergencies of national significance have increased in frequency over the last decade. Century-old policies tying wildland fire suppression responsibilities to the function of forestry are becoming outdated as fire intensity has increased and wild lands have become interspersed with development. Ever-increasing numbers of fire emergencies on the National Forests have stretched the US Forest Service thin, pulling funding and personnel from other functions (Attias; Hughes; Milstein). Leaving emergency management in the control of an agency designed to handle forestry has led to both poor forestry and poor emergency management. To best serve the public, the US Forest Service should relinquish its fire suppression mission to local emergency management agencies.

Over most of North American history, range and forest fire was accepted as part of the natural landscape. As western populations expanded in the early 1900s, several tragic outcomes from unsuppressed wildland fires spurred the young US Forest Service to assume fire suppression as a mission, with dispersed efforts nationwide coalescing into a national program over the first decades of the agency. With occasional and notable exceptions, fighting wildland fire on the national forests through the 20th century was a job dissimilar to fighting fire in an urban environment. Wildland fires posing imminent threat to civilian lives and private property were exceptional. The vast majority of wildland fire incidents were not emergencies as such, and suppression work on those fires was appropriately considered an extension of forestry. In the first decades of the Forest Service, fires were fought by all agency employees as a collateral duty, rather than by firefighters per se. The vast majority of Forest fires remained isolated from population centers and fires were handled less as an imminent emergency and more as a matter of timber resource management (Pyne 3-4; Aplet). Times have changed; in 2009, 1 in 3 Forest Service employees are wildland firefighters, and 42% of the agency’s 2010 budget is allocated to firefighting (United States “Overview” 14;”Fiscal” I1) .

The National Forests have undergone major changes in the last century of aggressive fire suppression. Modern foresters and ecologists understand the role of periodic fire in maintaining forest health. Ironically, fire suppression in most forest ecosystems leads to a buildup of flammable undergrowth, drastically intensifying the fires that eventually occur (Grahame and Thomas). Drought has stressed timber while pine-bark beetle infestations have spread throughout the west (Johnson; Meerik). National Interagency Fire Center statistics show that several of the most severe fire seasons in US history have occurred in the last 10 years, with several consecutive season totals approaching an unprecedented 10 million acres (U.S. NIFC).

While the National Forests have undergone changes, the lands adjacent to public forests have also undergone significant changes. The numbers of residents under potential threat from wildland fires on US Forest Service land has skyrocketed (“United States Housing”; US DOA and US DOI). Expanding suburbs have pushed ever closer to National Forest boundaries, the aesthetic appeal of forested property frequently taking priority over exposure to devastating wildland fire. Populated areas intermingled with areas of wildland fuels, collectively known as the wildland-urban-interface (or WUI), have proven a significant problem for both wildland fire management agencies and emergency management agencies. Efforts to mitigate WUI fire hazards to residents and firefighters have been undertaken nationwide, with varying levels of success (Nasiatka and Christensen “Wildland Urban”).

With a combination of increasing frequency of extreme fire behavior in the National Forests, and increasing public exposure to wildland fire, comes a dramatic increase in fire incidents which must be treated as emergency situations. Tactical approaches to engaging a wildland fire threatening life and/or private property differ significantly from approaches to a wildland fire threatening strictly or mostly natural resource values. We can see the results of those differences by comparing two similar fires: the Krassel Complex and the Castle Rock fire, both occurring in the mountains of central Idaho in September of 2007. The 56,000 acre Krassel Complex showed a more traditional model of the Forest Service fire: on Sept. 17th it was staffed with 73 personnel, 4 crews, a helicopter, and had a cumulative cost to the taxpayer of $2.1 million—the major values at risk being timber and several structures. The Castle Rock fire, however, threatened hundreds of homes and businesses in the WUI area surrounding Ketchum, ID; its 48,000 acres being staffed by 1517 personnel, 41 hand crews, 90 fire engines, and 19 helicopters, at a cost 10 times that of the Krassel (NIFC 1).

Under current operating principles, WUI fires require an abundance of staff from both traditional emergency management (structural fire departments, law enforcement, and emergency medical resources) and wildland-fire-specific resources (hotshot crews, helitack, wildland fire engines and incident management teams) due to the inability of either side to do the work of the other (National Wildfire “Fire Operations” p1.11). Much greater efficiency in operations could be achieved simply by integrating functions, so that all firefighters are trained to handle structure fire, wildland fire, medical emergencies, crash rescue, hazardous materials and coordination with law enforcement agencies.

-

07-01-2021, 06:53 PM #304

The duplication of effort goes beyond individual incidents. The split between wildland fire management and emergency management is a jackpot of duplicated effort at the program level. Forest Service Chief Dale Bosworth’s testimony before Congress in 2006 indicates the agency’s 2005 push toward administrative consolidation saved taxpayers $241 million (par 8). These savings have been achieved by integrating duplicated efforts within the Forest Service; yet these savings represent a small portion of what could be saved by consolidating duplication of effort across agency lines, integrating such functions as program administration, dispatching, information management, fleet management, budgeting and accounting, training, and human resource management.

To understand the Forest Service fire organization, one must recognize a major fundamental challenge of wildland fire management: efficiently allocating the down time associated with wildland fire. During severe seasons, with many ongoing fires, Forest Service fire resources are fully utilized in their designated roles; yet the seasonal and sporadic nature of these events dictates that most wildland firefighters will spend a significant amount of work time unassigned to fire incidents, and at times see long waits between responses. Currently, rather than serving in other kinds of emergency response when not engaged with wildland fire, Forest Service wildland firefighters build trail, cut and plant trees, maintain campgrounds, and perform any number of basic maintenance functions on Forest Service lands and facilities (Prentiss 3).

Using fire personnel as the catch-all work crew in the National Forests creates significant issues. Forest Service fire personnel who spend most of their work time doing forestry work have much less practice with emergency situations than even firefighters in relatively low-call-volume fire departments. A cursory Google search of “fire department call volume” allows one to scan call volumes for fire departments across the U.S. The low end of these figures is in the neighborhood of 50 emergency responses per year, while the higher end is in the thousands of responses per year. Surveying 15 wildland firefighters with tenure ranging from a decade to retired after 30 plus years of wildland fire service indicated career totals averaging 15-30 wildland incidents per year. With only a portion of wildland fire incidents being emergencies, clearly traditional emergency management organizations provide a better training platform for emergency response and offer personnel more opportunity to maintain acquired skill sets.

With a relative abundance of fire personnel and funding, a considerable amount of the Forest Service’s need for basic labor is being filled by highly-trained individuals hired, trained, and paid as firefighters. The difference in taxpayer cost between sending a $20,000 pickup truck with laborers to complete a basic task versus sending a fire-ready $100,000 emergency vehicle with firefighters is significant. Also significant is the overall lack of firefighter interest in and dedication to the work of forestry. Trail crews pride themselves on expert trail building, groundskeepers pride themselves on skilled landscaping; firefighters pride themselves on firefighting. Project work fills down time, serves agency objectives, and supports physical fitness but is frequently not undertaken with an adequate degree of task ownership. Additionally, with such an emphasis on project work, personnel may advance in the organization based on an aptitude for project work rather than an aptitude for firefighting, creating a chain of command unprepared to function optimally in emergency situations.

When the public funds a Forest Service fire position, they get a firefighter who makes a firefighting wage but spends most days working as a laborer rather than responding to, or even being available to respond to most public emergencies. Taxpayers purchase, stock, staff, and maintain Forest Service fire equipment that is not made available to assist with crash rescue or structural fire. Most of what the public gets from these expenditures is very expensive transportation for very expensive laborers to and from poorly executed busy work.

Structural fire departments, by contrast, partake in a wide variety of emergency response throughout the year, remaining sharp with standard procedures while developing and maintaining a holistic fluency with emergency situations. Under the current model most of the Forest Service firefighters managing the first significant forest fire of any given season have not been involved in a single fire response in the 5 or 6 month winter off-season. Incorporating Forest Service fires into emergency management’s mission would ensure that every incident is managed and staffed by personnel who have been responding to a variety of emergencies on a continuing and ongoing basis throughout their careers.

It is a fundamentally simpler proposition to ask emergency management organizations to apply their expertise to wildland fire than to continue relying on a forestry agency to adequately manage large emergencies. The public should have a reasonable expectation of well-rounded firefighters capable of handling all phases of the complex emergencies that exist in the modern Wildland Urban Interface. The public should also demand a forest service unencumbered by the budgetary and organizational demands of firefighting. In seeking to improve both emergency management and forestry service to the public, the path is clear: the US Forest Service must focus on forestry, and the emergency management agencies must absorb responsibility for firefighting on the National Forests.

-

07-01-2021, 06:53 PM #305

Works Cited

Aplet, Gregory H. “Evolution of Wilderness Fire Policy.” International Journal of Wilderness. 12.1 (2006):

9-13. Web. 9 Nov 2009.

Attias, Melissa. "Cash vs. Ash: A Losing Battle." CQ Weekly. 67.33 (2009): 1936. Academic Search

Premier. EBSCO. Web. 31 Oct. 2009.

Bosworth, Dale. Testimony: Statement of Chief Dale Bosworth United States Department of Agriculture

Forest Service Before the United States Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee Concerning the Forest Service Fiscal Year 2007 Budget. 28 Feb. 2006. USDA Forest Service. Web. 9 Nov. 2009. <http://www.fs.fed.us/congress/109/senate/budgetary/bosworth/022806.html>

“Forest Profiles: Ranotta McNair, Idaho Panhandle Forests Supervisor.” Forest Profiles. Idaho Forest

Products Commission. n.d. Web. 9 Nov. 2009.

<http://www.idahoforests.org/profiles/mcnair.htm>

Grahame, John D. and Thomas D. Sisk, ed. 2002. “Wildfire History and Ecology on the Colorado Plateau.”

Canyons, cultures and environmental change: An introduction to the land-use history of the Colorado Plateau. 5 Nov. 2009. <http://www.cpluhna.nau.edu/Biota/wildfire.htm>.

Hughes, Trevor. "Fire season forces $400M in cuts at Forest Service." USA Today. n.d. Academic Search

Premier. EBSCO. Web. 31 Oct. 2009.

Johnson, Kirk. "Beetles Add New Dynamic to Forest Fire Control Efforts." New York Times. 28 June 2009:

21. Academic Search Premier. EBSCO. Web. 9 Nov. 2009.

Meerik, Dave. “Fire Behaviour [sic]/Safety in Mountain Pine Beetle Killed Lodgepole Pine Stands in

British Columbia.” IAWF Conferences. International Association of Wildland Fire. Web. 5 Nov. 2009. <http://www.iawfonline.org/summit/2003.php>

Milstein, Michael. "Firefighting burns through forest funds." The Oregonian. 11 Aug. 2008. ProQuest.

Web. 9 Nov. 20

Nasiatka, Paula, and Christenson, Dave. "Wildland Urban Interface (WUI) Lessons Learned." Scratchline.

7 May 2007: 1-7. Web. 31 Oct 2009.

<http://www.wildfirelessons.net/documents/Scratchline_Issue19.pdf>.

---. "Line Officer Lessons Learned." Scratchline. 27 Nov 2006: 1-8. Web. 31 Oct 2009.

<http://www.wildfirelessons.net/docum...ne_Issue18.pdf >.

National Wildfire Coordinating Group (NWCG). Fire Operations in the Wildland/Urban Interface: S-215

Student Guide. Boise, ID. NFES. 2003. Print.

Prentiss, Matt. Wyoming Hotshot Summary Report: 2009 Fire Season. 15 Oct. 2009. Web. 30 Nov. 2009.

<www.wyominghotshots.com/files/2009_annual_report.doc>.

Pyne, Stephen J. "An Exchange for All Things? An Inquiry into the Scholarship of Fire." Australian

Geographical Studies 39.1 (2001): 1. Academic Search Premier. EBSCO. Web. 11 Nov. 2009.

Reardon, John A. "Unified Command and Shifting Priorities." Fire Engineering 158.8 (2005): 75-78.

Academic Search Premier. EBSCO. Web. 31 Oct. 2009.

Salt Lake County, Utah. “District 2: Michael H. Jensen.” Salt Lake County. n.d. Web. 8 Nov.2009.

<http://www.council.slco.org/html/mJensen.html>.

U.S. Dept. of Agriculture and U.S. Dept. of the Interior. 2001. “Urban Wildland Interface

Communities Within The Vicinity Of Federal Lands That Are At High Risk From Wildfire.” Federal Register 66: 751.

U. S. Dept. of Agriculture. Forest Service. Fiscal Year 2010 President’s Budget Overview. n.d.

USDA Forest Service, Web. 31 Oct 2009. <http://www.fs.fed.us/publications/budget-2010/overview-fy-2010-budget-request.pdf>.

U. S. National Interagency Fire Center. Fire Information – Wildland Fire Statistics. n.d. National

Interagency Fire Center. Web. 31 Oct 2009. <http://www.nifc.gov/fire_info/fire_stats.htm >.

U.S. National Interagency Coordination Center. Incident Management Situation Report. 2 Sep 2007.

National Interagency Fire Center. Web. 4 Nov. 2009. <http://www.nifc.gov/nicc/IMSR/2007/20070902IMSR.pdf>.

“United States Housing Density Maps and Data: animate 1940-2030.” Map. Housing Density Data. Dept.

of Forest and Wildlife Ecology, SILVIS Lab, University of Wisconsin Madison. n. d. Web. 11 Nov. 2009. <ftp://forest.wisc.edu/SILVIS/data/Ma...bg00_1940-2030

-

07-01-2021, 08:13 PM #306

Registered User

Registered User

- Join Date

- Oct 2010

- Posts

- 2,044

Wildfire 2021

Photo from Lytton BC. Wow. Estimated 90% of structures lost.

Story on the fire: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/briti...2021-1.6087311

-

07-01-2021, 09:49 PM #307

Man…that’s just horrific.

I’m so sorry.

-

07-02-2021, 03:39 AM #308

Registered User

Registered User

- Join Date

- Dec 2008

- Posts

- 866

IAS - that's a great piece and an interesting perspective. Thanks for posting.

You have some of the best outdoor writing I've stumbled across in the last years. I'd pay to read stuff like that combined with your other musings...

-

07-02-2021, 07:57 AM #309

-

07-02-2021, 09:04 AM #310

Registered User

Registered User

- Join Date

- Mar 2008

- Location

- northern BC

- Posts

- 34,019

They interviewd the Lytton fire chief he said the fire just raced thru the town, no way to stop it , at least 2 dead,

the thing that has always struck me with Lytton is that its always Hot , Dry, Windy

steep valley with 1 highway in or out of townLee Lau - xxx-er is the laziest Asian canuck I know

-

07-02-2021, 09:16 AM #311

Well written, IAS.

That’s terrible about Lytton.

-

07-02-2021, 09:31 AM #312

Well there goes our blue skies. Was a nice summer while it lasted. Fuck.

www.skevikskis.com Check em out!

-

07-02-2021, 09:39 AM #313

Registered User

Registered User

- Join Date

- Mar 2008

- Location

- northern BC

- Posts

- 34,019

some how the heat moved east & south so its sunny & 22, beautiful up here no smoke perfect biking weather , not sure why but I will take it

Lee Lau - xxx-er is the laziest Asian canuck I know

-

07-02-2021, 09:43 AM #314

Pyrocumulonimbus on the fire north of Walhachin, British Columbia.

“When you see something that is not right, not just, not fair, you have a moral obligation to say something. To do something." Rep. John Lewis

“When you see something that is not right, not just, not fair, you have a moral obligation to say something. To do something." Rep. John Lewis

Kindness is a bridge between all people

Dunkin’ Donuts Worker Dances With Customer Who Has Autism

-

07-02-2021, 09:51 AM #315

2 highways - #1 and #12. Exits to the south (Boston Bar), east (Spences Bridge to either Kamloops or Merritt) and north (Lillooet) out of town. Not fast highways, but gorgeous drives at any other time. Crazy times as the rivers flowing through the canyon (Fraser and Thompson) are absolutely swollen right now due to the extreme heat. Some places are getting baked and roasted, while others are flooded.

The t-storms that tracked thought the southern interior last night were scary impressive. We'll see what got sparked today, beyond those already reported in Kamloops and Castlegar. Forecast shows cooler and overcast skies by the middle of next week with some precip. Lets hope that forecast hold true.Last edited by BCMtnHound; 07-02-2021 at 10:18 AM.

-

07-02-2021, 09:55 AM #316

The Sparks Lk fire. Been burning for a few days, caused the t-storm system that sparked all the fires between Bonaparte Lk and Canim Night before last. I might be heading out this weekend to assist in the evacuations up along Hwy24. We've got friends and co-workers with homes and cabins in the Inter-Lakes area. Whatever didn't get burnt in the Elephant Hill fire in 2017

-

07-02-2021, 10:15 AM #317

On NPR Morning Edition today - Biden Vows to Boost Firefighter Pay Amid Staffing Shortages and Low Morale.

https://www.npr.org/programs/morning-edition/

-

07-02-2021, 10:20 AM #318

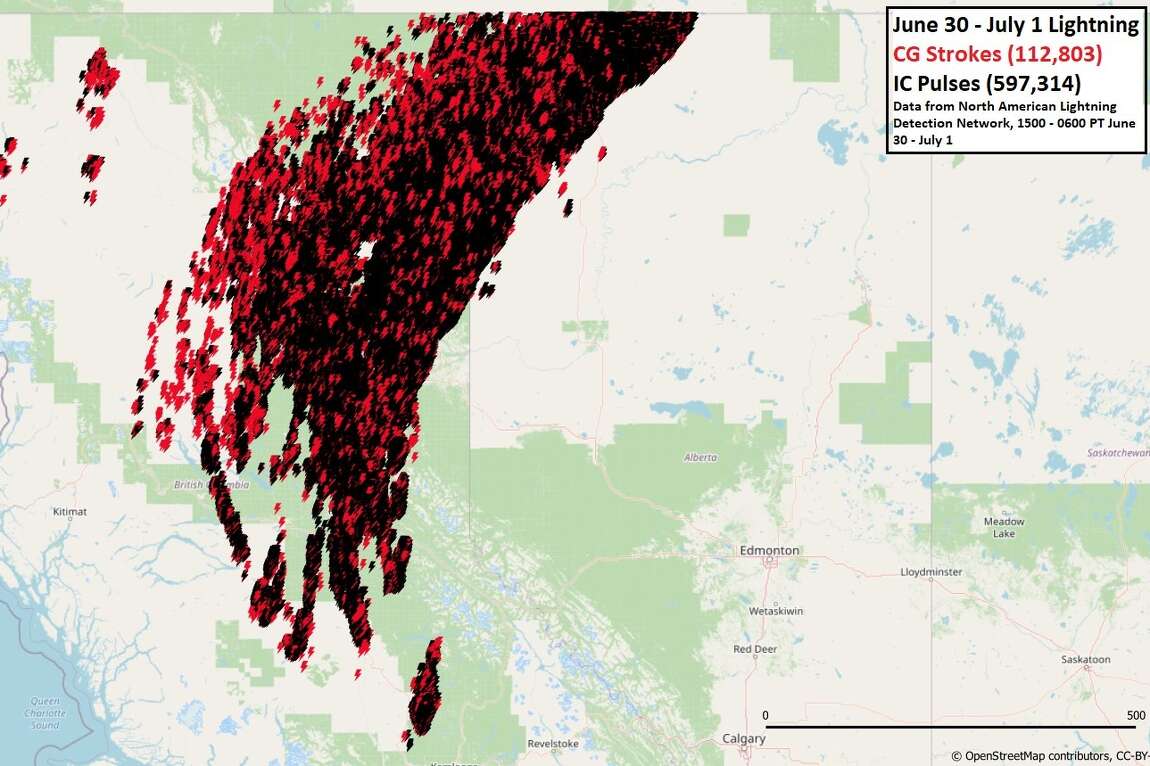

We are so fucked. Tons of lightning last night made for cool boat ride home but check out the map, so many north of Kamloops.

https://governmentofbc.maps.arcgis.c...2ee385abe2a41bwww.skevikskis.com Check em out!

-

07-02-2021, 10:25 AM #319

You were on a boat for the lightning?

Please be careful, if anything happens to your wife we’ll be devastated.

Sent from my iPhone using TGR Forums

-

07-02-2021, 10:39 AM #320

And most of those are from the t-storm I described above and discovered on Jun 30th. Very little updates yet for those sparked from last night's t-storm. That map could look very ugly by the evening.

Here's a screen capture from just one of the t-storm cells last evening in the North Adams area just east of me (in my work area):

And here's another:

-

07-02-2021, 10:53 AM #321

Registered User

Registered User

- Join Date

- Mar 2008

- Location

- northern BC

- Posts

- 34,019

those are 2 lane roads really, even hy 1 is just barely a highway in that area

I have been blown up river, sandstorms in mid river every time i paddled the thompson its size grandeur and extremes impressed me but apparently the fire jumped the river

edit: everything is pretty chill around here but i looked up to see an electra with the purple belly on final approach going in for another load,

I imagine a crew of Air tractors will show up pretty quick, they like to drink craft brew at the Bulkley after a long day of bombing firesLast edited by XXX-er; 07-02-2021 at 01:33 PM.

Lee Lau - xxx-er is the laziest Asian canuck I know

-

07-02-2021, 02:26 PM #322

-

07-03-2021, 09:51 AM #323“When you see something that is not right, not just, not fair, you have a moral obligation to say something. To do something." Rep. John Lewis

Kindness is a bridge between all people

Dunkin’ Donuts Worker Dances With Customer Who Has Autism

-

07-04-2021, 01:37 PM #324

click here

click here

- Join Date

- Oct 2008

- Location

- valley of the heart's delight

- Posts

- 2,602

-

07-04-2021, 01:46 PM #325

Wildfire 2021

Looks like the trestle in Stand By Me. Right location.

I guess not, it’s on the other side of the mountain

Sent from my iPhone using TGR Forums

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote

Bookmarks